Section 6. Responsibility for an application for international protection

The objective of the Dublin III Regulation is to guarantee that each person has effective access to the asylum procedure and that each application will be examined by one Member State only. To this end, the regulation establishes a set of hierarchical criteria under Chapter III to determine the Member State which is responsible for the examination of an asylum application.

The AMMR, which will replace the Dublin III Regulation by July 2026, clarifies the responsibility criteria and streamlines the rules for the determination of responsibility for an application for international protection. The criterion of the presence of family members is still emphasised in determining responsibility, and family cases are prioritised while providing applicants with more information and legal support. The regulation also introduces provisions to foster solidarity with Member States that are under disproportionate migratory pressure. The new Solidarity Mechanism foresees mandatory expressions of solidarity to support Member States while offering flexibility in contributions.

In crisis or force majeure situations, the Crisis and Force Majeure Regulation allows for deviations from the rules of the AMMR.

In 2024, EU+ countries continued to enhance the effectiveness of the Dublin III Regulation. For example, the implementation of the Dublin Roadmap, which was adopted in November 2022 to improve the implementation of Dublin transfers, continued throughout 2024. See Figure 10 for some of the achievements made by EU+ countries.

Figure 10. Examples of national developments in reaching the objectives of the Dublin Roadmap, 2024

Objective 1 - Limiting absconding

|

Focus on information provision on the responsible EU+ country (i.e. swift interview after transfers decision, use of Dublin transfer fact sheets) | Austria, Denmark, Netherlands |

|

Focus on improving the process for applying detention and alternatives to detention | Czechia, Luxembourg, Sweden |

Objective 2 - Improving communications between Member States

|

Use of liaison officers | Austria, Germany, Netherlands, Spain |

|

Bilateral agreements | Austria, Germany, Netherlands, Poland, Romania |

Objective 3 - Overcoming practical obstacles when implementing transfers

|

Charter flights | Austria, Ireland, Luxembourg |

|

Reduced notification period for incoming transfers | Hungary |

|

|

Enhanced cooperation with police | Spain, Luxembourg, Sweden |

Objective 4 - Ensuring sufficient resources to effectively implement Dublin transfers

|

Significant increase in the number of staff | Finland, Ireland |

Objective 5 - Increasing compliance with EU law, including court rulings

|

Specialised court unit for the Dublin procedure | Austria |

|

|

Making updated information available for courts through revised Dublin transfer fact sheets | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Germany, Greece, Spain, Finland, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden |

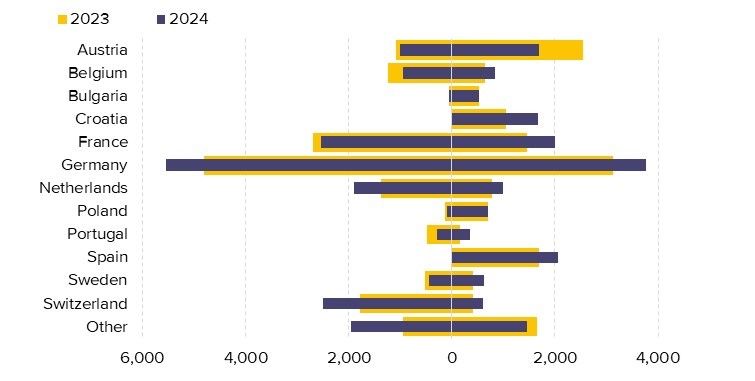

In total, 17,000 Dublin transfers were implemented in 2024, representing about a 14% increase compared to 2023. This was the most since 2019, while still far below pre-pandemic levels. Several reporting countries implemented more transfers than in 2023, with some implementing the most transfers on record, such as Cyprus, Estonia, Ireland, Norway and Slovenia. As in 2023, the top implementing countries were Germany (with 5,500 transfers), France (2,500), Switzerland (2,500) and the Netherlands (1,900).

- Germany, France and Switzerland carried out the most transfers.

- Germany, Spain and France received the most transfers.

- Afghans, Syrians, Algerians and Turks were the nationality groups transferred the most often.

Germany also continued to be the top receiving country (with 3,800 transfers), followed by Spain (2,100) and France (2,000) (see Figure 11). Transfers to Croatia and Latvia grew to the highest on record, while transfers to Austria fell by one-third. Overall, in 2024 Austria received more transfers than it carried out to other countries (as was the case in 2022 and 2023). However, this trend started to change in August 2024, and more transfers were carried out to other countries than transfers received to Austria. Transfers to Italy remained very low due to the circular issued by the Italian Dublin unit at the end of 2022, which was still in place, that incoming transfers were temporarily suspended except for the reunification of unaccompanied minors with their family. At the end of 2024, during a press conference after a working meeting with the Swiss Head of the Federal Department of Justice and Police, the Italian Minister of the Interior announced that he was willing to engage in discussions on resuming transfers with EU+ countries.302

Figure 11. Number of outgoing Dublin transfers implemented by sending (left) and receiving (right) country for selected countries, 2024 compared to 2023

EU+ countries further invested in digitalisation and ICT projects, either specifically for Dublin units or as part of larger initiatives involving asylum or immigration processes in general. For example, an automated process was piloted in the Netherlands to close Dublin cases in the IT system and automatically generate related correspondence. The Irish Dublin unit digitalised its paper files and made applications digitally available on a new portal. It also started to issue Dublin transfer decisions electronically. The unit noted that these developments helped to decrease processing times. The Dublin module was under development in the Belgian Immigration Office, as part of a wider digitalisation project called E-migration.

Cooperation among EU+ countries continued beyond the formalised channels of liaison officers and bilateral agreements. Several EU+ countries participated in 2024 in an EUAA exchange programme on effective family reunification. Bilateral study visits allowed specific countries to further strengthen their collaboration, such as the visit from the Romanian General Inspectorate for Immigration (GII) to the Swedish SMA. The GII delegation gained insights on the organisation of the Dublin unit and the procedure followed in Sweden, which can be used to reinforce processes in Romania.

EU+ countries reported that the caseload of Dublin units remained stable while most continued to face various challenges. To this end, the EUAA provided operational support for the implementation of the Dublin III Regulation in eight EU+ countries throughout 2024. The support included tasks at various stages of the Dublin procedure in Cyprus, Greece, Germany, Italy, Malta and Slovenia. Romania received support to optimise its Dublin workflows, while in Bulgaria, it consisted of the completion of Dublin-related administrative tasks.

A shortage of staff remained an important concern, in particular for Dublin units in Germany, Norway and Spain. To address the issue, Ireland’s Dublin unit recruited new staff and has planned further increases in 2025. Likewise, the Dublin unit in Spain recruited more staff and planned more increases before the Pact enters into application in 2026. In Italy, the high turnover of staff was reported to be the most significant issue. The Dublin unit in Finland faced challenges in having a sufficient number of trained staff.

In 2024, 147,000 decisions were issued in response to outgoing Dublin requests, according to provisional data which are regularly exchanged between the EUAA and 29 EU+ countries.ivThis represented an 18% decrease from 2023 when there were a record number of decisions, because asylum applications dropped by over one-tenth and the ratio of Dublin decisions to applications decreased to 14% (the lowest in 8 years). The decrease suggests a reduction in the number of asylum seekers moving from the first country of arrival to another to lodge a new application (referred to as secondary movements) and, accordingly, an impact on asylum caseloads overall.

Among EU+ countries receiving the most decisions on Dublin requests in 2024, several experienced declines compared to 2023 (see Figure 12, left panel), in particular Austria (65% less), France (35% less) and Slovenia (41% less). Conversely, decisions on requests issued by Italy and Norway rose by 18% and 23%, respectively.

For Dublin decisions issued, the most notable decline was in Austria, which issued more than 60% less than in 2023. This decrease was mainly due to high numbers in 2022 and 2023, and overall the number of decisions issued remained at a moderate level. This was followed by Romania issuing more than one-half fewer decisions, and Bulgaria and Croatia with about one-third less (see Figure 12, right panel). Greece, on the other hand, recorded a spike in decisions as they doubled compared to 2023. As in the past, more decisions were issued than received in Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia and Italy, and vice versa in countries in Central and Western Europe.

Figure 12. Top 10 EU+ countries by Dublin decisions issued and received, 2024 compared to 2023 and share of decisions issued from total decisions in 2024

Source: EUAA EPS data as of 3 February 2025.

In the second half of the year, EU+ countries started preparations for the implementation of the AMMR. Civil society organisations, for example ECRE, welcomed the new solidarity mechanism, but argued for a complete overhaul of the criteria to identify the Member State responsible for an asylum application.303 To support the implementation of the Pact at the national level, the EUAA started to work on new information provision leaflets on the AMMR and Eurodac, new guidance and a common template on family tracing, as well as guidance on remote interviewing (including for Dublin interviews).

In 2024, Dublin units adapted processes in response to judgments delivered by the CJEU in 2023 and 2022. Nonetheless, some ambiguities remained. The implementation of the 2022 CJEU judgment in C-19/21, which allowed unaccompanied minors to appeal the refusal of a take charge request in family reunification cases, still remained challenging for many countries. For example, the Dublin unit in Italy was waiting for guidance from the judicial branch on this matter. Likewise, the CJEU decision on the ‘chain rule’ was delivered in 2023, but questions remained around the responsibility determination procedure, both in legal and practical terms. The European Commission and the EUAA provided support to EU+ countries on these issues. The judgment, along with C-753/22, also led to an increased exchange of information requests based on the Dublin III Regulation, Article 34, adding to the workload of Dublin units.

In 2024, the CJEU delivered five judgments related to the Dublin III Regulation: deliberating on the principle of interstate trust (C-392/22), whether an effective remedy against a decision not to apply the discretionary clause should be available (C-359/22), examining an application when the applicant is already a beneficiary of international protection in another Member State but cannot be readmitted (C-753/22), potential release of a person who is kept detained based on two consecutive detention measures on different legal grounds (C-387/24), and situations when a Member State suspends the acceptance of a transfer for an indefinite period of time (C-185/24 and C-189/24). Adhering to case C-753/22, in particular, requires national authorities to reflect on revising their practices to take full account of another Member State’s decision to grant international protection when taking their own decision on an application. While this did not change the rules for determining responsibility, it has led to an increased number of information requests and increased workload for Dublin units. The judgment in case C-359/22 had a noted impact on the practice in Ireland, as Dublin transfers can now be enforced even when the application on the discretionary clause is pending a judicial or ministerial review.

Among case law from national courts presented in the EUAA Case Law Database for 2024 (see Table 5), the vast majority concerned transfers to specific countries, including to Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Spain. Only a few courts did not confirm the transfer but typically referred the case back to the lower instance or the national authority for failing to sufficiently investigate the specific circumstances for the possibility of implementing the transfer in each individual case.304

Table 5. Topic of court cases related to the Dublin procedure, 2024

| Dublin transfers to specific countries | Application of the discretionary clause | Principle of interstate mutual trust | Information provision on the Dublin procedure |

| Suspensive effect of a review | Language of the procedure | Incorrect information in a take charge request | Impact of failure to transfer within the time limits |

| Scope of judicial review under the Dublin III Regulation | Assessing differences in protection policies | Definition of family member under the Dublin III Regulation |

|

In several cases, the courts found that the applicants would be at risk of treatment contrary to the EU Charter, Article 4 if sent back to Hungary, due to systemic deficiencies in the asylum procedure.305Similarly, the Danish Refugee Appeals Board noted that it was highly unlikely that Italian authorities would issue individual guarantees when they currently receive a very limited number of transfers. Thus, the board overturned the transfers to Italy.306

Other court cases concerned the application of the discretionary clause in the Dublin III Regulation,307 such as two cases in front of the Italian Supreme Court which deliberated on the links between the Dublin procedure and the procedure to grant national forms of protection. The cases were referred for further assessment by the court’s United Sections, due to the importance of the matter.308

The Dutch Council of State delivered noteworthy judgments concluding that national authorities cannot rely solely on the principle of mutual trust for age assessments309 and that the failure to transfer an applicant within the time limits of the Dublin III Regulation did not mean that the original application for international protection ceased. In addition, the date of the original application for international protection is the one to take into account for the residence permit.310

The Italian Court of Cassation ruled that the failure by the national authority to comply with the obligation to provide information specifically on the Dublin procedure led to the annulment of a transfer decision.311

For more information, see Analysis of Jurisprudence on the Implementation of the Dublin Procedure, Fact Sheet No 33

- 302

State Secretariat for Migration | Staatssekretariat für Migration | Secrétariat d’État aux migrations | Segreteria di Stato della migrazione. (2024, November 26). L’Italie prête à discuter de la reprise des transferts Dublin [Italy ready to discuss resumption of Dublin transfers].

- iv

Greece did not report on Dublin indicators in 2024.

- 303

European Council on Refugees and Exiles. (May 2024). ECRE Comments on the Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Asylum and Migration Management, amending Regulations (EU) 2021/1147 and (EE) 2021/1060 and repealing Regulation (EU) No 604/2013

- 304

Slovenia, Supreme Court [Vrhovno sodišče], Applicant v Ministry of the Interior (Ministrstvo za notranje zadeve‚ Slovenia), VS00075109, ECLI:SI:VSRS:2024:I.UP.86.2024, 22 April 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Slovenia, Supreme Court [Vrhovno sodišče], Ministry of the Interior (Ministrstvo za notranje zadeve‚ Slovenia) v Applicant, VS00076907, ECLI:SI:VSRS:2024:I.UP.146.2024, 28 June 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Netherlands, Court of The Hague [Rechtbank Den Haag], State Secretary for Justice and Security (Staatssecretaris van Justitie en Veiligheid) v Applicant, NL24.17079, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2024:8634, 29 May 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Norway, District Court [Noreg Domstolar], Applicant v Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda‚ UNE), TOSL-2024-41013, 5 July 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 305

Germany, Regional Administrative Court [Verwaltungsgericht], Applicant v BAMF, No 12 K 2146/24.A, 10 October 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Luxembourg, Administrative Tribunal [Tribunal administratif], Applicant v Ministry of Home Affairs (Ministère des Affaires Intérieures), No 50847, ECLI:LU:TADM:2024:50847, 30 August 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Luxembourg, Administrative Tribunal [Tribunal administratif], Applicant v Ministry of Home Affairs (Ministère des Affaires Intérieures), No 50977, ECLI:LU:TADM:2024:50977, 20 September 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Czechia, Supreme Administrative Court [Nejvyšší správní soud], 2 Azs 134/2024 - 31, 28 August 2024.

- 306

Danish Refugee Appeals Board | Flygtningenævnet. (2024, December 3). Flygtningenævnet har truffet afgørelse i klagesager efter Dublinforordningen vedrørende de generelle forhold for asylansøgere i Italien [The Refugee Board has made decisions in appeal cases under the Dublin Regulation regarding the general conditions for asylum seekers in Italy].

- 307

Ireland, High Court, PZ v The International Protection Appeals Tribunal & Ors, [2024] IEHC 88, 31 January 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Ireland, High Court, AC v International Protection Appeals Tribunal & Ors, [2024] IEHC 77, 12 February 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Italy, Supreme Court of Cassation - Civil section [Corte Supreme di Cassazione], Ministry of the Interior (Ministero dell'Interno) v A.S., R.G 10898/2024, 5 April 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Italy, Supreme Court of Cassation - Civil section [Corte Supreme di Cassazione], Ministry of the Interior (Ministero dell'Interno) v H.A., R.G 10903/2024, 5 April 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Ireland, High Court, S.P. v Minister for Justice & Ors, [2024] IEHC 479, 29 July 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 308

Italy, Supreme Court of Cassation - Civil section [Corte Supreme di Cassazione], Ministry of the Interior (Ministero dell'Interno) v A.S., R.G 10898/2024, 5 April 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Italy, Supreme Court of Cassation - Civil section [Corte Supreme di Cassazione], Ministry of the Interior (Ministero dell'Interno) v H.A., R.G 10903/2024, 5 April 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 309

Netherlands, Council of State [Afdeling Bestuursrechtspraak van de Raad van State], Applicant v The Minister for Asylum and Migration (de Minister van Asiel en Migratie), 202201742/1/V2, ECLI:NL:RVS:2024:3992, 9 October 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 310

Netherlands, Council of State [Afdeling Bestuursrechtspraak van de Raad van State], Applicant v State Secretary for Justice and Security (Staatssecretaris van Justitie en Veiligheid), 202107377/1/V1, ECLI:NL:RVS:2024:881, 4 March 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.

- 311

Italy, Supreme Court of Cassation - Civil section [Corte Supreme di Cassazione], Applicant v Ministry of the Interior (Ministero dell'Interno), R.G. 10331/2024, 3 April 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database. Italy, Supreme Court of Cassation - Civil section [Corte Supreme di Cassazione], Applicant v Ministry of the Interior (Ministero dell'Interno), R.G. 11000/2024, 3 April 2024. Link redirects to the English summary in the EUAA Case Law Database.